“Our fragile planet is hanging by a thread” – Guterres

“Our fragile planet is hanging by a thread.” Antonio Guterres, UN Secretary General, has summarised succinctly, in this phrase, the threatened future of the planet following the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow.

Countries emerged with a deal – the Glasgow Climate Pact – that was better than no deal and has been characterised as a ‘bridge’ to more ambitious action. COP26 President Alok Sharma revealed that at one point, it seemed a collective document would unravel completely.

However, for the most climate-vulnerable countries, the massive gap in overall climate finance and the still-inadequate action by large emitters to cut greenhouse gases by 2030 leave the Earth on ‘code red’ alert. CASA’s Mairi Dupar reports.

There is a massive amount of work still to do, following COP26, in order to:

- Provide climate finance at the level needed for a rapid transition to a truly low-carbon, climate-resilient future – rich countries failed to reach the promised $100 billion per year in climate finance that was due to be disbursed by 2020; the Africa Group of Negotiators is calling for a step change, and flows of $1.3 trillion in climate finance annually by 2030.

- Provide loss and damage finance to climate-vulnerable countries to enable them to recover from the devastating impacts of climate change that they are already suffering today.

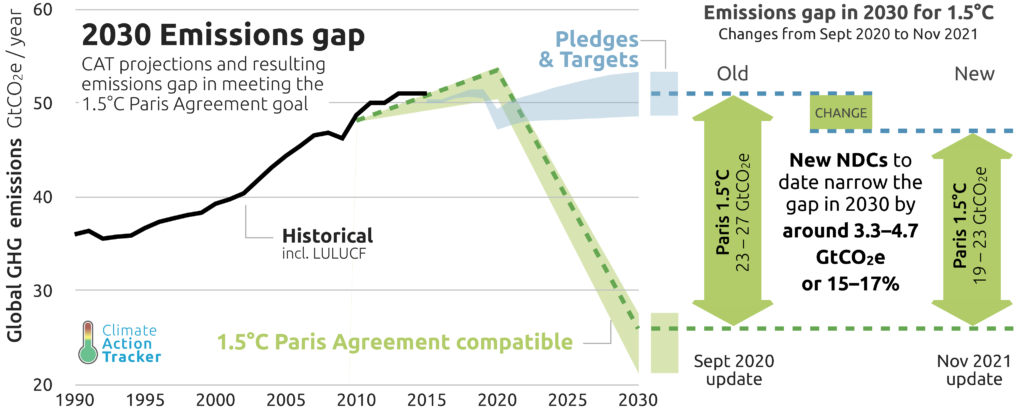

- Shift global emissions onto a pathway to a 1.5°C world. Even with new pledges and updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) announced in the run-up to COP26, collective ambition puts the world on a pathway to well above 2 degrees (see more, below).

These necessary steps have been deferred to 2022-23. The Glasgow Climate Pact reaffirms the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature goal. It stresses that “limiting global warming to 1.5°C requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, including reducing global carbon dioxide emissions by 45 per cent by 2030” which “requires accelerated action in this critical decade.”

The final decision of the Parties calls on governments to revisit and submit more ambitious NDCs in 2022 to align with the temperature goal — in time for COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt.

Mr Guterres has meanwhile vowed to convene world leaders in 2023 for a stock-taking summit and to establish a High Level Expert Group on calculating the emissions reductions of non-state actors. This complements the UNFCCC’s Global Stocktake process.

Youth activist: ‘Humanity cannot survive on promises – prove us wrong’

The Glasgow Climate Pact highlights the impacts of climate change on young people and it acknowledges the heightened climate activism of young people, children and civil society.

The Pact calls for Parties to “respect, promote and consider… intergenerational equity” in governmental climate actions.

One of COP26’s most memorable speeches was by Ugandan youth activist Vanessa Nakate – with words to resonate in delegates’ minds for the months and years ahead.

Referring to the failed promise of the $100 billion in climate finance, Ms Nakate said:

“Humanity cannot survive on promises. It is hard to believe finance and business leaders when they have not delivered before….I am here to ask business and finance leaders: show us your faithfulness, show us your trustworthiness, show us your honesty. I am here to say: prove us wrong.”

‘Rulebook’ for implementing the Paris Agreement is finalised

There was some good news arising from the technical detail of the Glasgow talks. Parties to the Paris Agreement finally agreed on the outstanding procedures for implementing the agreement, known in shorthand as the ‘Paris Rulebook’.

Article 6: Carbon markets. Countries agreed on how international carbon markets would function (Article 6) – although some controversies remained.

“In Glasgow, we have fought hard to ensure market mechanisms deliver true environmental gains, while also supporting vulnerable countries to meet their adaptation costs,” stated H.E. Sonam P. Wangdi, Chair of the LDC Group.

In reference to the final article 6.4 text about a multilateral carbon credit mechanism, Mr Wangdi commented: “The remaining carbon budget does not have space to carry forward old emission reductions credits, and we are disappointed the rules do not reflect this.” The final rules allow carbon credits registered under the Clean Development Mechanism after 2013 to count towards current NDCs under the Paris Agreement.

(For an excellent explainer on the Article 6 carbon markets decisions, see Steve Zwick’s article on Ecosystem Marketplace.)

“On Article 6, we need to remain vigilant against greenwashing, protect environmental integrity and human rights and the rights of indigenous people,” cautioned Marshall Island Climate Envoy and High Ambition Coalition spokeswoman Tina Stege.

Enhanced Transparency Framework: reporting tables. Countries will report on their climate actions using the Enhanced Transparency Framework, which was agreed in Katowice in 2018. Talks in Glasgow settled the outstanding details of how those reporting tables will be formatted.

Because developing countries face capacity constraints in their abilities to gather and report high quality information, the decision allows for developing country Parties to have some flexibility “when reporting on a provision for which they have a capacity constraint.”

Parties encouraged the Global Environment Facility to provide funding specifically for these reporting capacities.

Some progress on adaptation finance

Climate-vulnerable countries have long decried the gap in adaptation financing: it has comprised only 21% of total climate finance from high-income to low- and mid-income countries, in the context of insufficient climate finance overall.

The Glasgow Climate Pact now secures an agreement for adaptation financing to be doubled by 2025, based on 2019 levels.

“Within the High Ambition Coalition, we campaigned hard from dawn to dusk to secure a doubling of adaptation financing. When the High Ambition Coalition launched this call, we didn’t know if it would be possible, it was a very hard-fought win,” said Tina Stege, Marshall Islands Climate Envoy, on twitter.

The Pact moreover acknowledges that the most climate-vulnerable countries are not yet able to access the climate finance they need. The Pact:

“31. Notes the specific concerns raised with regard to eligibility and ability to access concessional forms of climate finance, and re-emphasizes the importance of the provision of scaled-up financial resources, taking into account the needs of developing country Parties that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change;

32. Encourages relevant providers of financial support to consider how vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change could be reflected in the provision and mobilization of concessional financial resources and how they could simplify and enhance access to finance.” (CMA3)

Dr Amal Lee Amin, a climate finance expert, remarked that the text builds on a 11 November IMF statement on the rechanneling of Special Drawing Rights to the neediest countries, and Dr Amin added that concessional finance “must be easy to access and non-conditional to reduce both costs of adaptation and economic losses.” (For a definition of Special Drawing Rights, see this IMF factsheet.)

Ambassador Janine Felson of Belize, said that climate vulnerable countries’ lack of access is often incorrectly framed as a ‘capacity’ challenge “but simply put, the finance institutions are not fit for purpose. They need to be reformed to be able to respond to the climate emergency we face.”

Meanwhile, COP26 established a two-year Glasgow-Sharm-el-Sheikh Work Programme on the Global Goal on Adaptation, to begin immediately, with the overarching purpose of “enabl[ing] the full and sustained implementation of the Paris Agreement, towards achieving the global goal on adaptation, with a view to enhancing adaptation action and support.”

Climate-vulnerable countries let down on loss and damage

The Scottish Government made waves by announcing the first bilateral funding pledge to address climate-related loss and damage from historic emissions. This was branded a significant and symbolic step that addressed a ‘taboo’ in climate funding.

In spite of this, other developed countries did not follow. Text in the Glasgow Climate Pact to strengthen the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage was limited to providing technical assistance.

“We are disappointed that the proposed Glasgow Loss and Damage Facility is not included in the final decision,” said H.E. Sonam P. Wangdi.

“Our people are already experiencing a mounting onslaught of loss and damage caused by climate change. We heard widespread recognition of this injustice, yet there was a failure to address it. Ensuring our communities are supported in addressing the loss and damage that the climate crisis inflicts on them remains a top priority.”

Massive shift needed to limit warming to 1.5 degrees

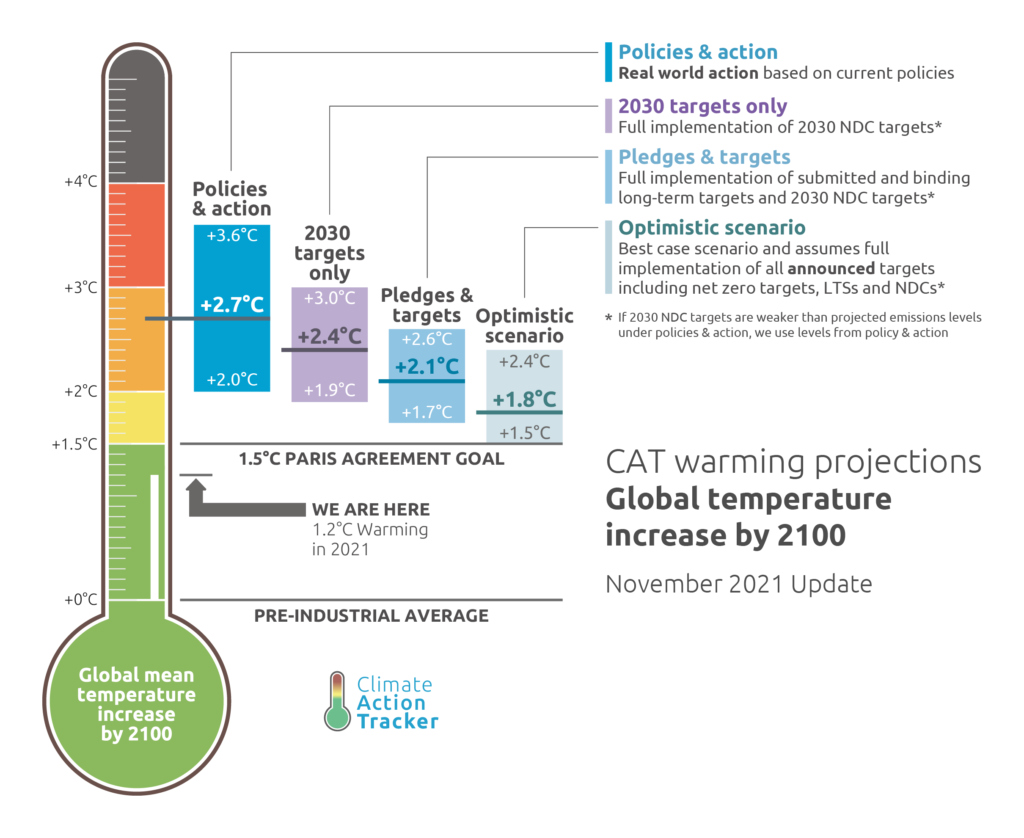

The authoritative Climate Action Tracker (New Climate Institute and Climate Analytics) issued a new analysis of climate targets, pledges and actual real-world policies to deliver on climate goals, mid-way through COP26. Their analysis makes for deeply disturbing reading. It states categorically that real-world policies for delivering emissions reduction are commensurate with around 2.7°C of global warming – which would be catastrophic for people and ecosystems.

One of the reasons for this huge alarm? Policies and actions for reducing emissions before 2030 are still so weak: even if many more countries have now declared net zero emissions targets for 2050 (which is aligned with the science), there is a finite carbon budget that can be spent before the 1.5°C global warming threshold is breached. It is imperative that deep and irreversible emissions cuts happen this year and in the years up to 2030, to ensure this carbon budget is not exhausted too fast.

“No single country that we analyse has sufficient short-term policies in place to put itself on track to its net zero target,” finds CAT. Furthermore, “2030 actions and targets are more often than not inconsistent with net zero goals.”

Although new initiatives were announced at COP26 to slash methane emissions and end and reverse deforestation by 2030, these initiatives need to prove they are truly new and additional if they are to change the temperature projections – CAT says.

Reaching higher

Much of the political narrative and media attention at COP26 was on the need to reduce polluting coal use as quickly as possible – and on the last-ditch request by China and India to change the final Glasgow text from ‘phasing out’ coal to ‘phasing down’ coal.

Costa Rican Environment Minister Andrea Meza and Danish Climate Minister Dan Jørgensen launched the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance to emphasise that action must go even further. Oil and gas will also need to be phased out to place the world on a Paris-compatible pathway (as Climate Action Tracker explains).

Oil and gas did not make it explicitly into the Glasgow Climate Pact but will demand essential attention as Parties reconsider their targets, pledges and actual policies — and regroup for climate talks in 2022.

H.E. Sonam P Wangdi, Chair of the LDC Group, concluded in his post-Summit remarks: “We have to acknowledge the final decision is far from enough to match the scale of the crisis and to meet the needs of our countries.”

“This next year will be critical in setting the trajectory for the decade. Increased ambition in mitigation, adaptation, and climate finance remains an urgent priority. We are running out of time and the work is not yet done.”

Image (top): Skyline beside the Scottish Exhibition Centre, Glasgow- Mairi Dupar, CASA